About the Scottish Maritime Museum

Hi! My name is Marta and I am a 3D Digitisation Project Manager at the Scottish Maritime Museum. I currently lead on a project called ‘Scanning The Horizon’ which aims to document in 3D the museum’s collection of large- and small-scale vessels, machine tools, and artefacts. The objects tell the seafaring story of Scotland, which was once the most important shipbuilding nation in the world.

The buildings and sites which the Scottish Maritime Museum occupies are themselves part of the heritage collection.

The Scottish Maritime Museum in Irvine is housed within the glass-roofed Victorian Linthouse building. It was formerly the Engine Shop of Alexander Stephen and Sons shipyard in Govan (Glasgow) before being salvaged and relocated to Irvine in 1991.

The Scottish Maritime Museum in Dumbarton features the world’s first commercial ship testing facility, the Denny Ship Model Experiment Tank, the last surviving part of the former Denny Shipyard.

About the Project

Seeking to promote the maritime and industrial heritage of Scotland, the Scottish Maritime Museum started looking into new ways of engagement with the public. Our mission is to keep the history of the Scottish shipbuilding industry alive, especially amongst younger audiences. Interactive 3D models seem ideal to encourage potential visitors to come to our museum and explore our collections in person. 3D models have become a fun way in which visitors can learn about museum collections. Increasing numbers of cultural institutions worldwide are using this new tool as an effective and engaging way of reaching new audiences. For us, apart from engaging with the public, there are three main strands to the project.

- First, we want to have an accurate record of our collection to allow our in-house staff to monitor the condition of the objects in our care.

- Second, we want to make our collections more accessible through modern digital methods.

- Third, we want to add a layer of storytelling to our digital collections, allowing our online viewers to discover the stories about the objects and learn about their past.

Workflows, Know-hows, and Challenges

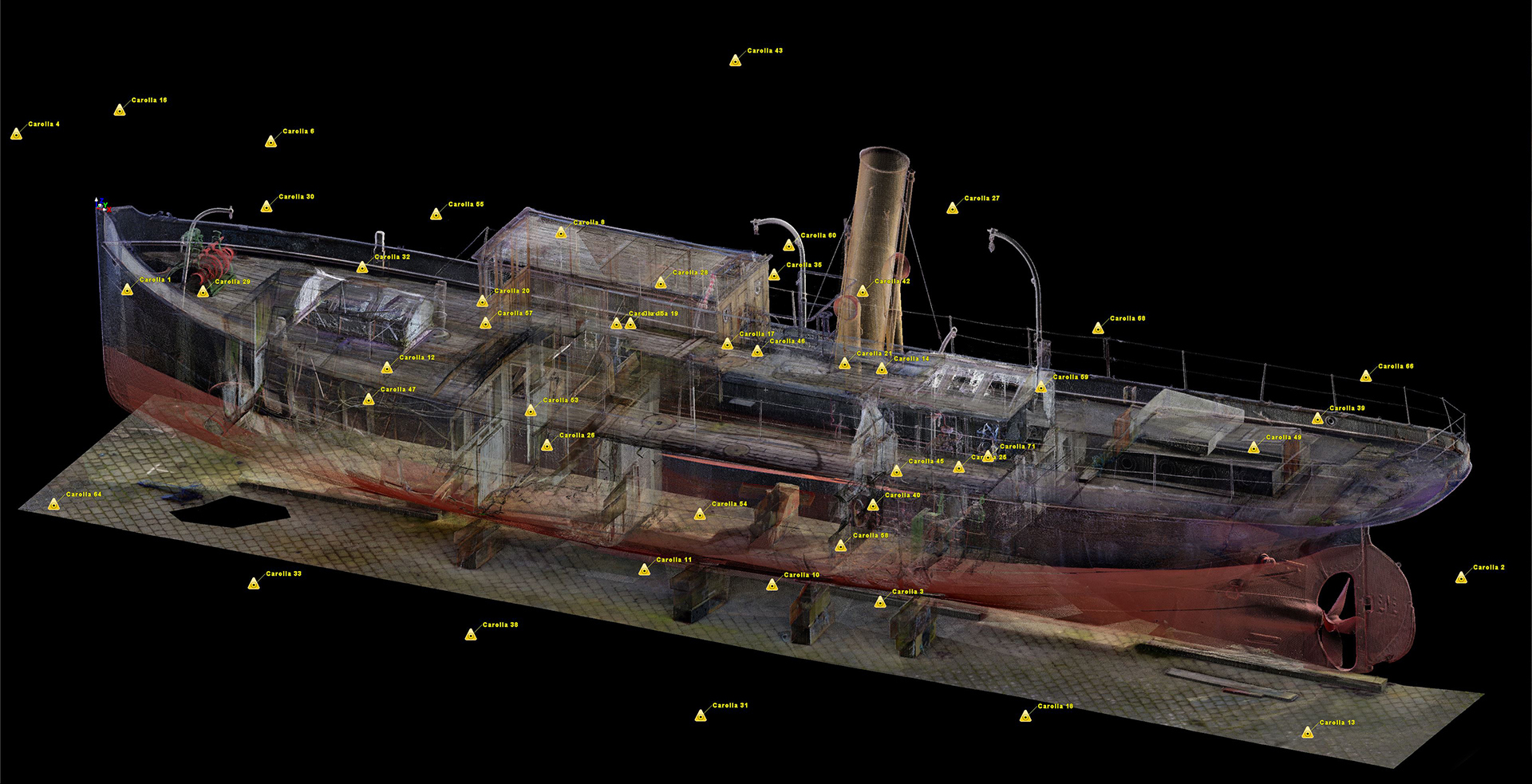

As you have probably guessed, the scale of the collection dictates the techniques that can be used to create 3D content in our museum. A combination of laser scanning and photogrammetry is being used to create deliverables for the project.

The workflow for our smaller collections is based on photogrammetry. The reason is very simple: availability on a budget. With a decent camera, a sharp lens and some photography know-how you should be ready to explore the world of 3D photogrammetry and build decent models fairly quickly.

However, the nature of our collections requires us to pursue more advanced setups when it comes to capturing 3D data for our large-scale collections. The steamers, puffers, engines and machine tools housed in our museum are in most cases metal objects, usually coated with shiny paint, often black. This combination can be quite a challenge when it comes to 3D data capture. Black and shiny objects don’t lend themselves well to either photogrammetry or laser scanning. To make it even more interesting, we can’t really put our large objects in a controlled-light studio environment, which means we are at the mercy of the elements.

Fear not, though! With enough patience, attention to detail, and good data overlap, there is a lot that can be done! By combining laser scanning and adding fill-in photogrammetry data we manage to get accurate 3D content from the scanner merged with good quality textures from photogrammetry.

Sounds simple? Well, in theory, it is! I must admit though, this project has been a steep learning curve when it comes to data capture and processing in an industrial heritage context. Not to mention working with objects that do not lend themselves well to 3D documentation methods! When photographing black surfaces, slightly overexposing images can make a difference.

Polarising filters can help when dealing with shiny materials, like polished metals or gilded sculptures. In reality, each object poses different challenges and requires a slightly different approach.

My standard workflow would involve:

- For laser scanning: capture with a focus on good overlap and clean, accurate data. Registration of the entire point cloud in dedicated software (usually Leica Cyclone). The merged registered point cloud can then be imported into photogrammetry software and combined with the photogrammetry dataset for further processing (adding fill-in data and high-quality textures).

- For photogrammetry: data capture focusing on good overlap and sharp, crisp images. When it comes to photogrammetry it’s worth remembering that it’s not only about capturing the object but about capturing its features, all of which may significantly help with the alignment.

I use RealityCapture (RC) for photogrammetry processing, as it allows me to get fantastic results and doesn’t require lengthy processing. It also allows me to merge the laser scan data with photogrammetry, which is a key functionality for this particular project. In RC, after initial alignment, I would decide which inputs (scans/ images) I want to use for further processing, whether it is meshing or texturing the model.

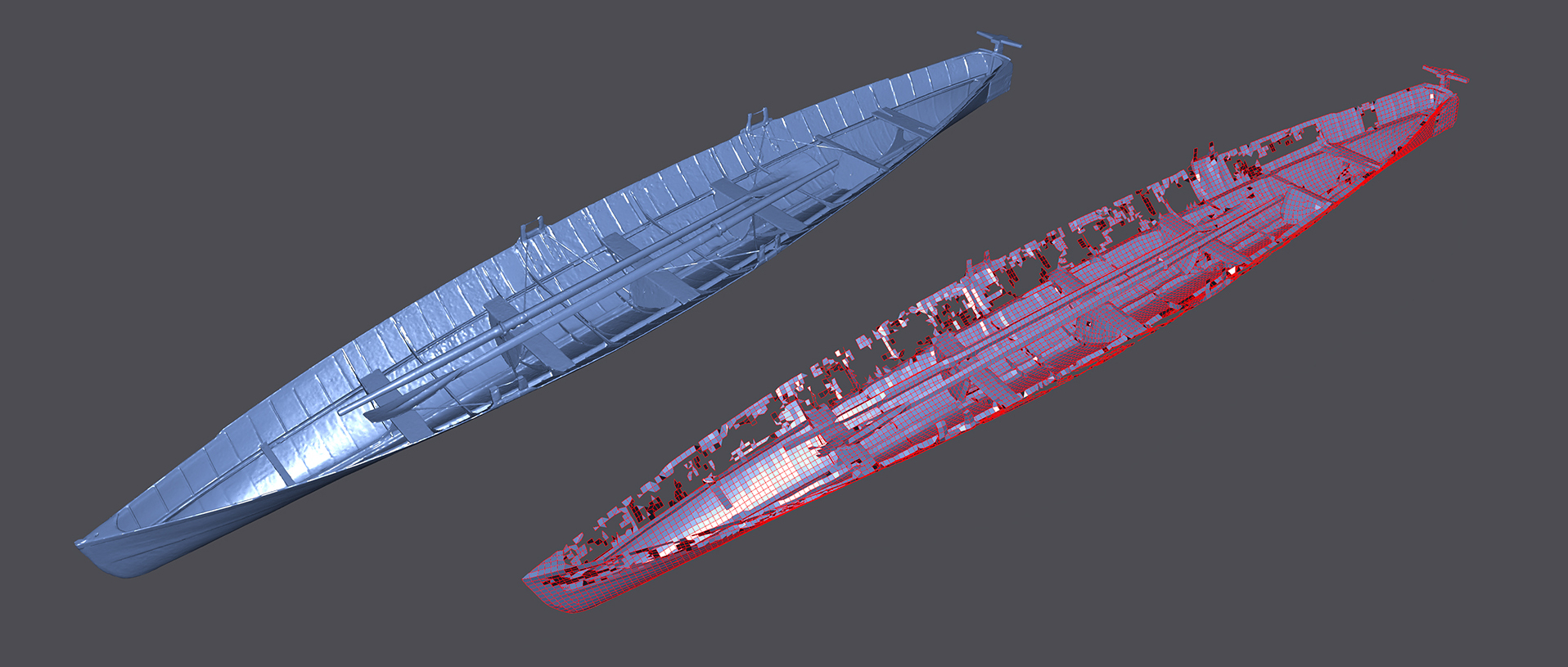

After surface reconstruction (meshing) the models would be very heavy as the polygon count would reach millions. Therefore, optimisation is always required to allow the objects to be viewed online.

This stage can be done inside RC, but external software packages can be used as well. For this collection, a combination of both is often required and using a test-and-trial approach proved effective to determine which option works best for each individual object.

Walls of the vessels can be quite thin, and that combined with the issue of black or shiny surfaces may sometimes lead to creating holes in the mesh.

This is an issue that some 3D packages can deal with better than others and therefore some flexibility in the workflow is always a good thing. I tend to use a combination of RC, 3ds Max, Instant Meshes, and Meshlab, depending on which one works best for which object. There is not really a right and wrong way here and (to be fair) most of the results can be achieved with all of these tools—the choice is simply a preference.

Once the face count is reduced, the model will most likely still require minor corrections, so after the final clean-up, it can be textured. For some time now, RC has a tool allowing you to reproject the high-quality maps onto the low poly models, a functionality which I absolutely love! Before I would use either render-to-texture in 3ds Max or would import the low poly model to xNormal for baking (the latter is always a great option as it’s completely free and allows you to get up to 32K resolution textures!).

The Role of Sketchfab

From the very beginning, it was obvious that we wanted to make our data available online and Sketchfab is the best way to do so. With an intuitive interface and friendly community, we knew that it’s a platform that will help us to promote the maritime heritage of Scotland.

In the 3D environment, we can not only showcase our collection and present it to a wider audience but also tell stories about these objects and add sound descriptions and images to create an even more engaging experience.

So far, the biggest milestone has been publishing the model of Spartan, the most important vessel from our collection and one of only two surviving Scottish-built ‘puffers’.

Thanks to Sketchfab, users can explore the 3D model and access areas of the vessel, which they otherwise could not visit due to health and safety restrictions surrounding access. This, combined with the virtual tour we launched on our website, expands the museum’s offer allowing the visitors to go up the deck and explore 360 panoramas from the comfort of their own device (and hopefully soon in VR in Irvine!).

Our 3D gallery is slowly growing and we are releasing new models on a regular basis. The next step for us will be adding this content to our museum space, allowing physical visitors to digitally engage with the collection and discover its history. Further down the line, we may also look at using AR and animations to show how shipbuilding machines from our collections work. The potential of using digital methods to enhance the museum experience is vast, so we are very excited about what the future may bring!

If you would like to keep track of what we publish, give our Sketchfab account a follow!

Find us on-line: Twitter / Facebook / Website

Scanning The Horizon 3D Digitisation Project is jointly funded by Museums Galleries Scotland and Scottish Maritime Museum Trust.

We would like to thank

Historic Environment Scotland,

Leica Geosystems,

Ulmus Media,

and RPS Europe

for their help during this project.