The COVID-19 pandemic turned teaching and research at West Virginia University on its head in March 2020 like it did for students and educators worldwide. My students and I are responsible for teaching mineralogy and petrology (the study of rocks, specifically) to 30–40 undergraduate students in the Geology and Mine Engineering programs, and we had to adapt quickly when our traditional in-person lab classes were suspended and instruction moved online.

Sketchfab immediately became our replacement for students to access mineral and rock samples from home so they could complete the course. This was an exciting challenge and demonstrates the enormous potential of novel online resources to supplement and, in some cases, replace traditional instructional techniques and to greatly expand the reach of classes and degrees that have typically been limited to on-campus, in-person curricula.

Where we started

I was first introduced to 3D modeling through my research work on how ancient rocks have been deformed—the field of structural geology. Structural geologists are interested in the geometries of rock bodies and features within them like faults; therefore, all structural geology has to be considered in 3D.

My research currently focuses on how viscous lavas flow using natural outcrops of ancient lavas. These ancient lavas form spectacular tongues of black obsidian glass and grey pumice that flowed away from the volcano, and many were sites where native people obtained obsidian for stone tools. Most are only a few hundred years old, so I use a drone to fly over them and to make new super-high-resolution maps of their surfaces. The same drone images are also used for Structure-from-Motion photogrammetry to build 3D outcrop models, for example, from the Big Obsidian Flow at Newberry caldera in central Oregon, U.S. and at Medicine Lake volcano in northern California. Whereas the new maps are used in the field to help guide data collection and locate our measurement sites, the 3D models themselves can be analyzed to collect data about structures over much larger areas than can be covered on foot, as well as features that are so large that they are missed by geologists on the ground.

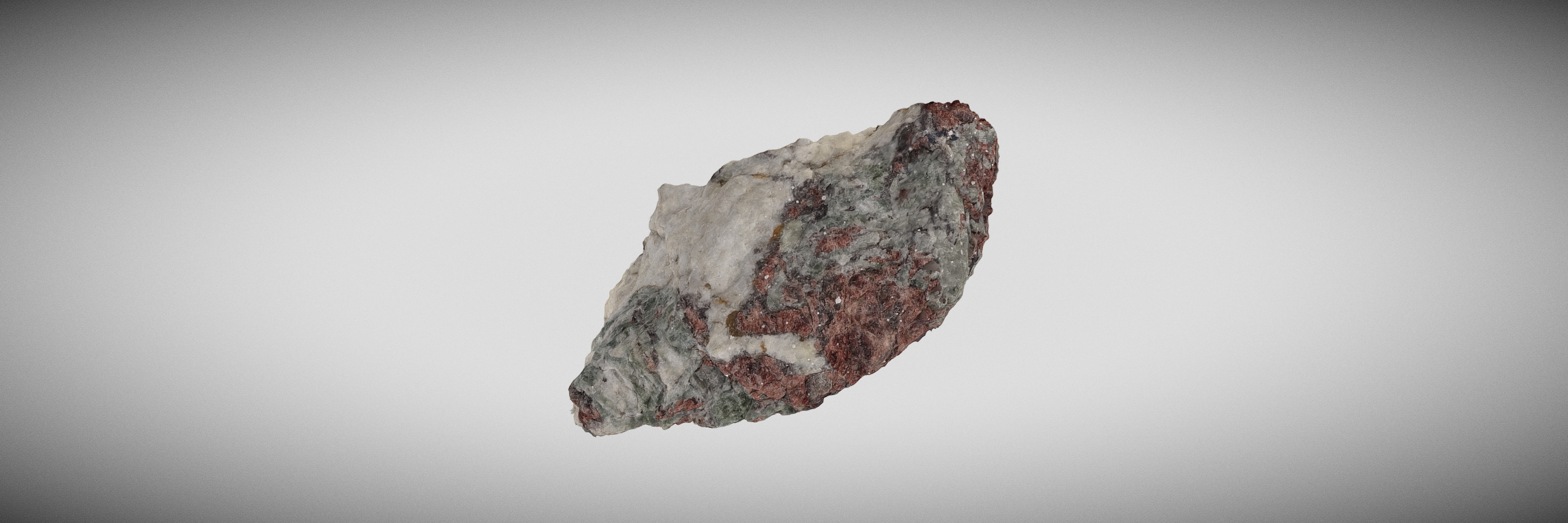

We immediately saw the benefits of cataloging interesting rock types and morphologies using photogrammetry, and the potential to share 3D rock models in our research and in teaching. Understanding volcanic rocks is dependent on documenting and interpreting the small-scale morphologies and textures of rock samples, which makes it difficult to adequately represent them with 2D photographs. Therefore, we set-out to establish a 3D digital atlas of volcanic rocks that could be made available for free through Sketchfab, using the large and growing collection of real samples we already had at WVU. We also used Sketchfab to host 3D models of a rock sample that we had analyzed by computed X-ray tomography in a paper in the free online journal GEOSPHERE. In this, we used Sketchfab to show both a photogrammetric model of the exterior and a segmented model of part of the sample’s interior from the X-ray data. An example of our lab’s models of rocks is this volcanic sample from Iceland:

March 2020

WVU classes were moved online with about two weeks notice in March 2020. I was then teaching two mineralogy and petrology classes, both with significant hands-on components where students would usually handle dozens of samples. Having students handle samples and conduct tests on them is seen as a key part of the training of geology students. So how can this experience be replicated online? Can it be done successfully?

Undergraduate researcher Gabrielle, my graduate students and teaching assistants Shelby and Holly, and I made a list of essential mineral and rock samples needed for our two classes. We then began constructing 3D models of specimens in our teaching collection and searching through Sketchfab for existing digital models. I then selected models to use in class and developed exercises around them. Using models on Sketchfab requires rethinking what we want students to understand and be tested upon, and how specific questions are asked. One particularly successful use of the models on Sketchfab is to link them to virtual fieldtrips designed in Google Earth or in online quizzes. Although not definitive, responses from students were uniformly positive about the Sketchfab models—the only complaint that I received was that I had access to too many models to assign to them.

Summer 2020

We were overwhelmed by the number and quality of models already available on Sketchfab and being developed in parallel with our efforts; so much so that it became a job just to keep up with new models being made around the world daily. It was clear that Sketchfab-hosted models were being made and used by their creators, but it wasn’t clear how many others were taking advantage of them. Based on our Spring 2020 experience and foreseeing that Autumn 2020 would be similar, we recognized the need to

- highlight the existence of 3D digital models to geology instructors,

- help them find the models they needed,

- assist new model-makers in getting started, and

- help them use the models in their classes.

On this basis, in July we and our colleagues at Kansas State University were awarded a National Science Foundation RAPID award to develop and advertise widely a catalog of Sketchfab geology models.

Hours of searching in Sketchfab for geological models highlighted to us the need to develop a searchable catalog where teachers can search using specific technical terms. The search bar within Sketchfab is surprisingly good but the diversity of models on Sketchfab, especially fictional and gaming-related models, can overwhelm searches for geological content. For example, a search for the mineral ‘garnet’ returns multiple models of a popular computer-game character before presenting a geological sample. Working remotely, two undergraduates, Anna and Ian, and I, took the models in my growing collections on Sketchfab, and built a searchable catalog in Google Sheets. In it, we split samples by their geological classifications and added minimal metadata and the URL. I participated in several informal online workshops over the summer to promote the new catalog and to demonstrate the utility of 3D models to instructors preparing for Autumn classes, and we advertised it widely on listservs and social media. Again, we didn’t collect hard data on how many people we reached, but my number of Sketchfab followers doubled and the catalog routinely had a dozen or so users each day in September.

Where we’re going

Together with Dr. Matt Brueseke at Kansas State University (on Sketchfab and Twitter), we are identifying gaps in the range of mineral and rock models on Sketchfab and attempting to plug them. We are also designing a WVU website to introduce new and future users to how to search for, build, and use 3D models in the geology classroom. We will highlight examples of how we have used Sketchfab models in our own classes and prepare curated ‘sets’ of models tailored to typical class exercises and exams.

Our goal is to make 3D models of rocks and minerals, and indeed outcrops and fossils too, into integral parts of the geology teacher’s tool-kit, not just as a Band-Aid during COVID-19. This approach is important to increase the reach and scope of geo-education at a time when enrollment in sciences is down but the number and severity of environmental challenges facing society are increasing. Many of the largest, and also richest and most prestigious universities, have extensive mineral and rock collections gathered in the last two centuries but unavailable to outside users. The majority of schools, colleges, and universities have small, often incomplete and generic collections that have been picked-over by students for decades or have lost their corresponding information. Home-educators and those looking to study geology in a non-traditional educational environment often have no access to collections at all. Using Sketchfab and 3D digital models goes a long, long way in addressing these inequities.

If you want to know more about our lab and research, you can find me on Twitter at @WVURockDoc and our lab’s website, our YouTube channel where we have some videos helping to explain photogrammetry and using Sketchfab, and, of course, on Sketchfab.