The Royal Museum for Central Africa: a museum and a research institute

The Royal Museum for Central Africa, together with the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, has been one of the pioneers in 3D digitization of the collections in museums in Belgium. Today, the museum uses several 3D digitization techniques on a daily basis: micro-computed tomography, structured light scanning, photogrammetry and multispectral photogrammetry.

The Royal Museum for Central Africa was created in 1898. Nowadays, it is one of the biggest research institutes and museums in the world with a focus on Africa. It holds remarkably diverse collections ranging from natural sciences to earth sciences and cultural heritage. In total, the collections are estimated to be 11 million specimens.

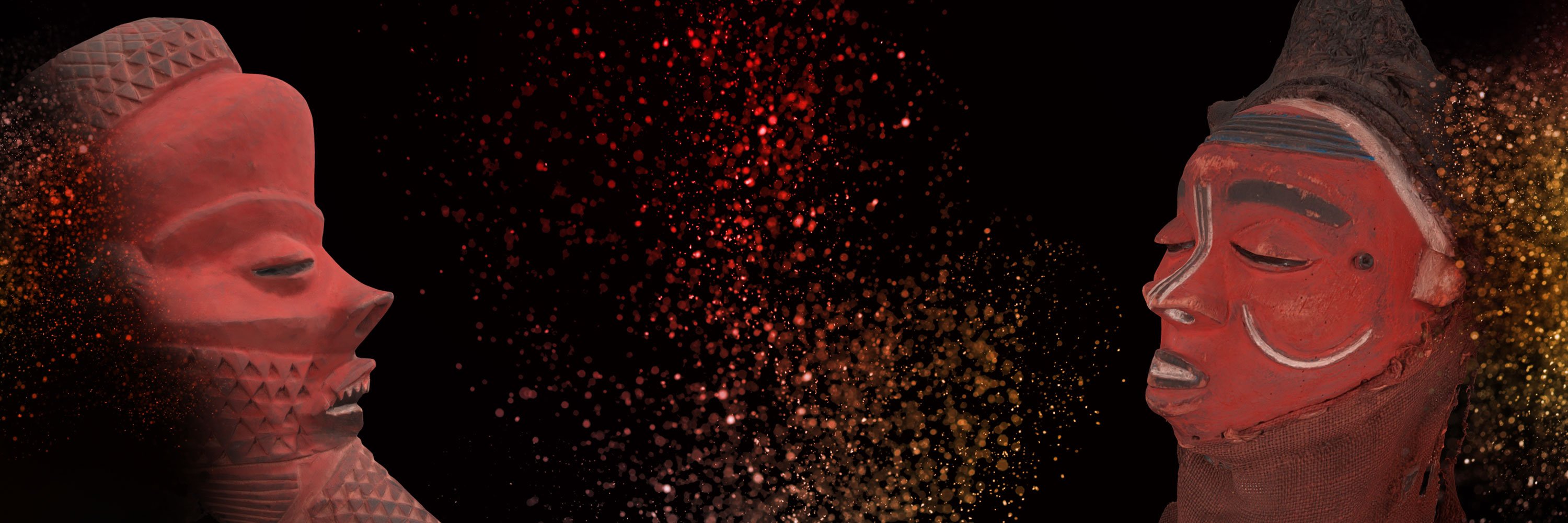

One of the flagship collections of the museum is the ethnographical collection and, more specifically, the Pende masks. The Pende’s or Bapende (plural of Pende) are a Bantu population, living in Central Africa (mainly Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola). They are renowned for their masks, which are made of wood and fibers and usually colored with red pigments.

Most of the masks that have been analyzed belong to the category of “mbuya” masks from central Pende. These masks link the living with the ancestors. They were worn in the framework of special occasions like the introduction ceremony of a King, at events marking the beginning of the agricultural season, or at the end of the male rite of passage.

The Pende mask project: 50 shades of red

In the framework of my Ph.D. on 3D multispectral digitization, I became interested in the potential of the technique to identify the pigments used. The Pende masks were a perfect case study as a camaieu of red pigments can be observed among the different masks; so far, very few studies have focused on the diversity of red pigments used. It was also the opportunity to digitize some of our most prestigious collections.

The masks were digitized using multispectral photogrammetry, which is basically classic photogrammetry using different light sources with specific wavelengths and filters. The masks were placed on an automatic turntable in a photographic studio with a controlled light environment. Each mask was digitized with between 108 and 180 pictures, depending on the complexity of the mask, for each wavelength. Nineteen wavelengths were captured per model, ranging from ultraviolet to infrared.

In order to be able to capture reflected ultraviolet and infrared, we used a modified camera (e.g. a camera where the infrared filter had been removed) together with an apochromatic multispectral lens.

Digitization of the masks was quite challenging as they are made partly of fibers that can move when the object is moved. The masks are quite fragile and therefore cannot be hanged with transparent nylon or held on a thin rod while captured; they had to remain on their support and each support is manufactured for the masks. Therefore, the inside or back structures of the masks are seldom captured.

Online publication: Collections behind the scenes

Collections of large museums like the Royal Museum for Central Africa are very vast. It is commonly recognized that only 5% of the collections of big museums are exhibited, while most of the collections remain hidden to the public. In the Royal Museum for Central Africa, only 1% of the collections are displayed over 11,000 m². That does not mean, however, that the rest of the collections are “sleeping” and collecting dust, waiting to be rediscovered. On the contrary, they are constantly being studied by scientists or sent on loan for temporary exhibition elsewhere. It has been the will of the Royal Museum for Central Africa to render their collection more accessible, to the public and scientists, by digitizing them and displaying them on public platforms like Sketchfab and our own website. All the models uploaded to Sketchfab are embedded on the virtual collections platform that offers more tools to research and navigate through the collections. 3D models are also linked to our scientific databases and are an integrated part of collections management.

To summarize, the 3D scans, or photogrammetry, of the objects in our collection are used for dissemination to the public, to give them a glimpse of our hidden treasures. They are also used for collections management and research, as is the case for the Pende masks. Additionally, models can be reproduced by 3D printing for educational purposes or to replace traditional casts. Casting is a contact technique that can sometimes be harmful or leave residues on the original object while 3D scanning and photogrammetry have the benefits of being contactless techniques.

Advice for beginners

Generally speaking, photogrammetry is the more versatile and affordable capture technique. It is accessible to anybody. Having basic photography knowledge is a plus. Equipment can also play a key role in the quality of your final acquisition: if you can easily obtain a 3D model with your smartphone, using a DSLR with a prime lens can drastically improve your 3D model.

Before digitizing an object, ask yourself why you want to digitize it, what is the purpose of your scan. For visualization purposes, photogrammetry is certainly the way to go as it allows you to obtain a photorealistic texture. If you are interested in internal structures, computed tomography might be a better option, but it’s far less accessible. Structured light scanning can be a more efficient solution, especially if photorealistic rendering is not important. Finally, terrestrial laser scanners will be more appropriate/efficient for large sites.

Gazing into the future

3D digitization of heritage has been booming during the pandemic as it was sometimes the only way to share the collections or to virtually visit remote sites. This is probably going to continue and 3D heritage will be more and more accessible in the near future.

While 3D digitization of a site or an object was something new and innovative 10 years ago, we can see today it is part of the daily workflow of many museums, ranging from small museums to the more renowned. Computers and tools are getting more performant and more accessible allowing the field to grow faster and faster. Additionally, the European Commission is pushing toward more digitization and toward open access.

One of the challenges that are facing scientists regarding this mass digitization is how to assess the accuracy and reliability of the 3D models.

But digitization is also a double-edged sword; if on one side, it gives easier access to the collections and sites, we must be careful that it does not replace the real objects and sites.

Share the love

One of my all-time favorite models on Sketchfab are the ants model made by Economolab. It allows you to see ants like never before, revealing the secrets of their microcosm. And maybe that’s what we should explore in the future: the microcosm of our heritage. What those things that are infinitely small and often overlooked, or restricted to the eyes of the specialist, can reveal about our past.

This article was written with the contribution of Julien Volper, ethnography curator at the Royal Museum for Central Africa.