The Project

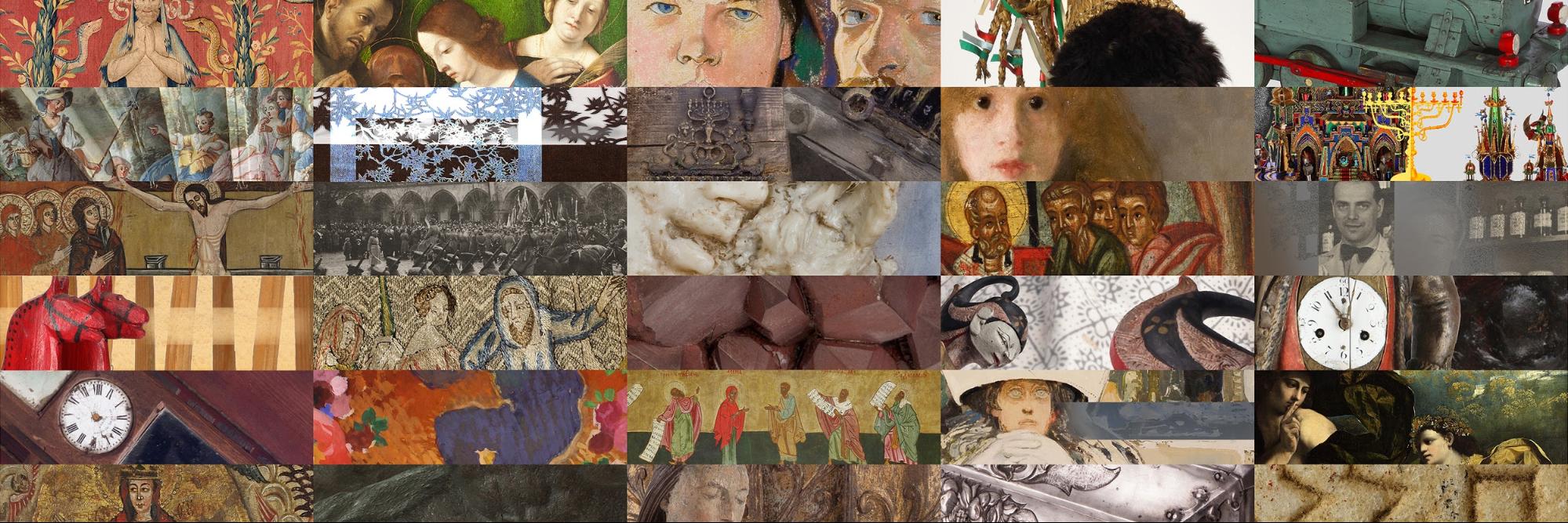

“Malopolska’s Virtual Museums” is one of the first attempts at digitising museum collections in Poland to be carried out on such a large scale. It stands out from other Polish projects involving museum exhibit digitisation, as it is mostly based on 3D technology – the Malopolska Museum currently has about 600 objects that can be seen in three dimensions on-line, and 1000 more 3D objects are to come in 2020.

Currently around 1000 exhibits (both 2D and 3D) from 40 museums are gathered on one website; it is not only a catalogue of exhibits containing three dimensional objects, high quality digital images, a lot of them in gigapixel resolution, but also extensive descriptive, contextual and educational materials, which makes it easier for viewers to interpret the gathered cultural heritage. With this website, it is possible to learn not only about the rich history of these artefacts, but also to see them up close, and to explore every tiny detail about them.

The website was created as part of a project implemented in partnership with the Economic Development Department of the Malopolska Province and the Malopolska Institute of Culture, in cooperation with 39 museums. The project was co-financed with resources from the European Regional Development Fund.

The website was established between 2012-2013, and currently is quite obsolete due to the technology which was used at the time (HTML 4.0, UNITY3D, FLASH). A new website and IT system is under development now, and should be revealed to the public in mid-2020.

Object-Centric Metamuseum with “Go Between Museums” Motto

On the Malopolska’s Virtual Museums internet portal, the focus is on objects (“exhibits”), not museums, art collections, preservation, history or art history. Emphasis is on all the meanings the objects can have, and how to show all the hidden or not so obvious connections between them. The digitisation process is the beginning of a new virtual life for cultural heritage objects, with the additional benefit of documentation and inventorisation. In our project, the goal of the digitisation is to show a virtual representation – an “idea” of the real object. Here is the list of museums in “Malopolska’s Virtual Museums.”

To achieve all of these goals, we have worked out the following complex process:

From Real to Digital: Process

The whole process of the “Malopolska’s Virtual Museums” project is divided into three main stages: digitisation, publication and interpretation.

Digitisation is the part of process consisting of the acquisition of all knowledge about the exhibits which is possible to acquire, and transferring it into the IT system. We get the colours and shapes of the objects with 3D scanning and photography, and we gather all the information surrounding the objects, not only based on the museum inventory card (size, date it was made, material, etc.) but also, we go further with our “Do you know, that…?” formula, which contains a more narrative description.

Publication is the part of the process involving putting all the gathered information into our repository system and showing it on-line in the form of an object card. We translate all text into English, and last but not least, we add audio descriptions. We’ve found audio descriptions valid not only for the vision-impaired, but also for children, because of the simple and precise spoken description. (“You’ve been told what you are looking at”). At this stage, our editorial team is connecting and linking objects from various museums at a more general level.

Interpretation, the most interesting part of the process, is the point of change: the real object is left in a real museum cabinet and it is translated into its infographic virtual representation. Now, as pure information, the object can be a part of mind maps different than in the real world. We invited famous Polish culture interpreters to write meaningful stories with the objects as actors. These stories are transformed into forms of multimedia presentations.

There is also an extra part of the process at Malopolska`s Virtual Museums which is undisclosed to the public – time consuming editing of 2D and 3D digitisation data into the form of 2D and 3D visualisations and editorial work on essential texts done by a group of 12 people:

The Team

A large digitisation project like this should be based on the skills of the people involved. The crew of Malopolska’s Virtual Museums project is divided into four teams. Digiteam is a mobile team of two photographers and a 3D scanner operator. 3Dteam is a team of three graphic designers that process data from digitisation. The other three people (Editorial Team) are editors involved in the substantive development of texts published on the portal, contact with museum partners, and the development of all metadata. There is also another three-person management team preparing digitisation projects according to the rules of the public procurement law in Poland. Some of the skills and competences of team members overlap each other. Photographers can edit 3D graphics, 3D graphic designers can help with photography or scanning, and a 3D scanner operator ensures proper data acquisition and that filenames and folder structures are in order.

The Team has to face the main characteristics of our subject:

The Variety of Museums. The Variety of Exhibits.

The variety of the presented collections is undoubtedly one of the greatest strengths of Malopolska’s Virtual Museums but, at the same time, it was a great challenge if one takes into consideration the technical aspects of the project. The digitisation process has to take place in each museum.

A repository of this kind, containing the collections of several dozen museums with such varied resources (works of art, industrial, archaeological, ethnographic and natural objects), gives an extraordinary range of options for the interpretation of the cultural heritage of the region. But at the same time, the exhibits are varied both in their content and their forms. Both large, like church altars, and smaller-sized objects like elements of jewelry and coins have been digitised; matte and shiny objects can be found here, and also those composed of many elements or constituting just a part of the exhibition. Exhibits from industrial production are in a category of their own.

Maybe the most demanding challenge was the digitisation of modern art objects, especially from the collection of the MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow, with as extraordinary artwork as the “Third Crop” by Teresa Murak – a dress with living and growing watercress seeds sown in it.

Also challenging, was another contemporary art collection from Bunkier Sztuki Contemporary Art Gallery, with artwork such as “Flashback Smurfs” by Maciej Chorąży or “Balance Beam #0715” by Vlatka Horvat. The results of this work are now available to view.

Bunkier Sztuki Gallery of Contemporary Art by Virtual Museums of Małopolska on Sketchfab

For modern art exhibits, the idea behind the artwork is often more important than the objects themselves.

Recently we added the Collection of the Sosenko Family Foundation, with classical beauties of perfume bottles:

https://sketchfab.com/WirtualneMuzeaMalopolski/collections/collection-of-the-sosenko-family-foundation

Our first solution for problems due to the wide variety of objects is:

Mobility of a Team

The diversity of the objects requires the adaptation of procedures to existing conditions and requires a lot of creativity during the digitisation process. It is connected mainly with work practices – every time, a slightly different mobile digitisation station is created in different museums.

- Fig. 1 Mobility of a team. The need to adapt to different requirements in different museums (Nowy Sacz District Museum).Photo by MIK.

- Fig. 3 Fig. 4. Mobility of a team. The need to adapt to different requirements in different museums (Wawel Royal Castle – State Art Collection).

- Fig. 2 Mobility of a team. The need to adapt to different requirements in different museums (Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow MOCAK. Photo by MIK.

Each time, slightly different conditions and limited time for data acquisition has a big impact on the digitisation process, and differs from museum-based digitisation workshops. At the same time, it also opens other opportunities: sometimes the “digiteam” comes to digitise only one bed, but ends up doing the whole room.

Due to its flexibility, our team is able to adapt to the specific conditions of each place. All of this has had a profound influence on the great success of the project.

The second solution for the challenge of the variety of exhibits is using an individual approach for each object, though we want to process the same type of information for each of them:

Process and Post-Process. Shape and Color.

In the “Malopolska’s Virtual Museums” project, the digitisation process is conducted with the use of a structured-light 3D scanner (HDI Advance, Artec Eva) as well as turntable sequences of photos (Canon EOS). The data obtained during the scanning process provides accurate information about the geometry of the exhibits. In this way, a spatial, multimillion set of measuring points creates 3D triangle meshes, while hundreds of high resolution photographs guarantee accurate information about the colour of the exhibits. Use of two data streams (3d scanning and multi-view photography) ensures the accuracy of the process. The last task to be completed by the Digiteam is to save all the data with valid file names. Proper handling of valid file names is probably the most important skill for any digitisation project.

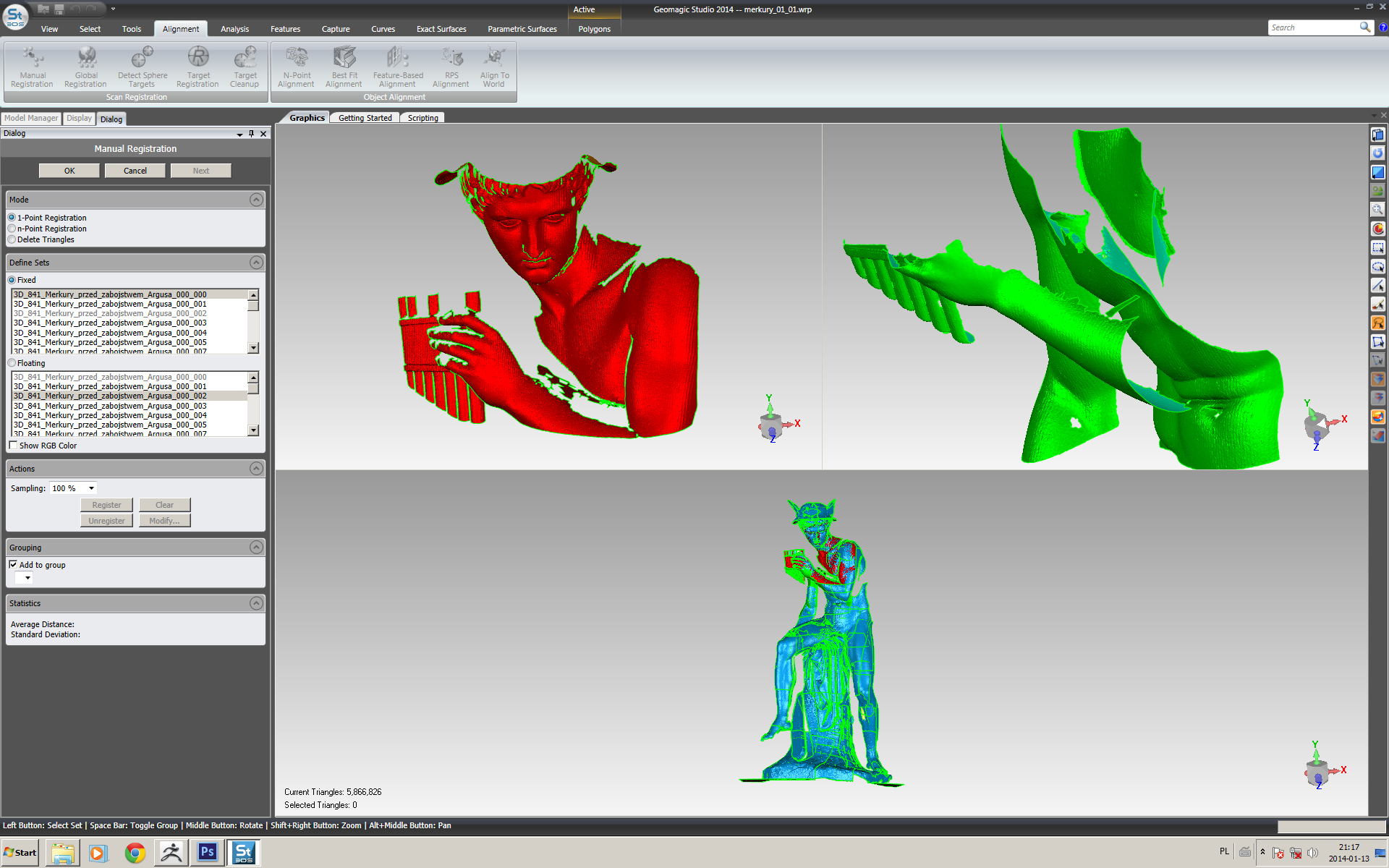

The first stream of data (3D scanning) is passed on to the 3D graphic designers, whose job it is to clean the high resolution dense meshes and turn them into editable 3D models. It is done with proprietary scanner software and Geomagic Wrap. At this stage, we get the 3D mesh properly measured, in a valid scale.

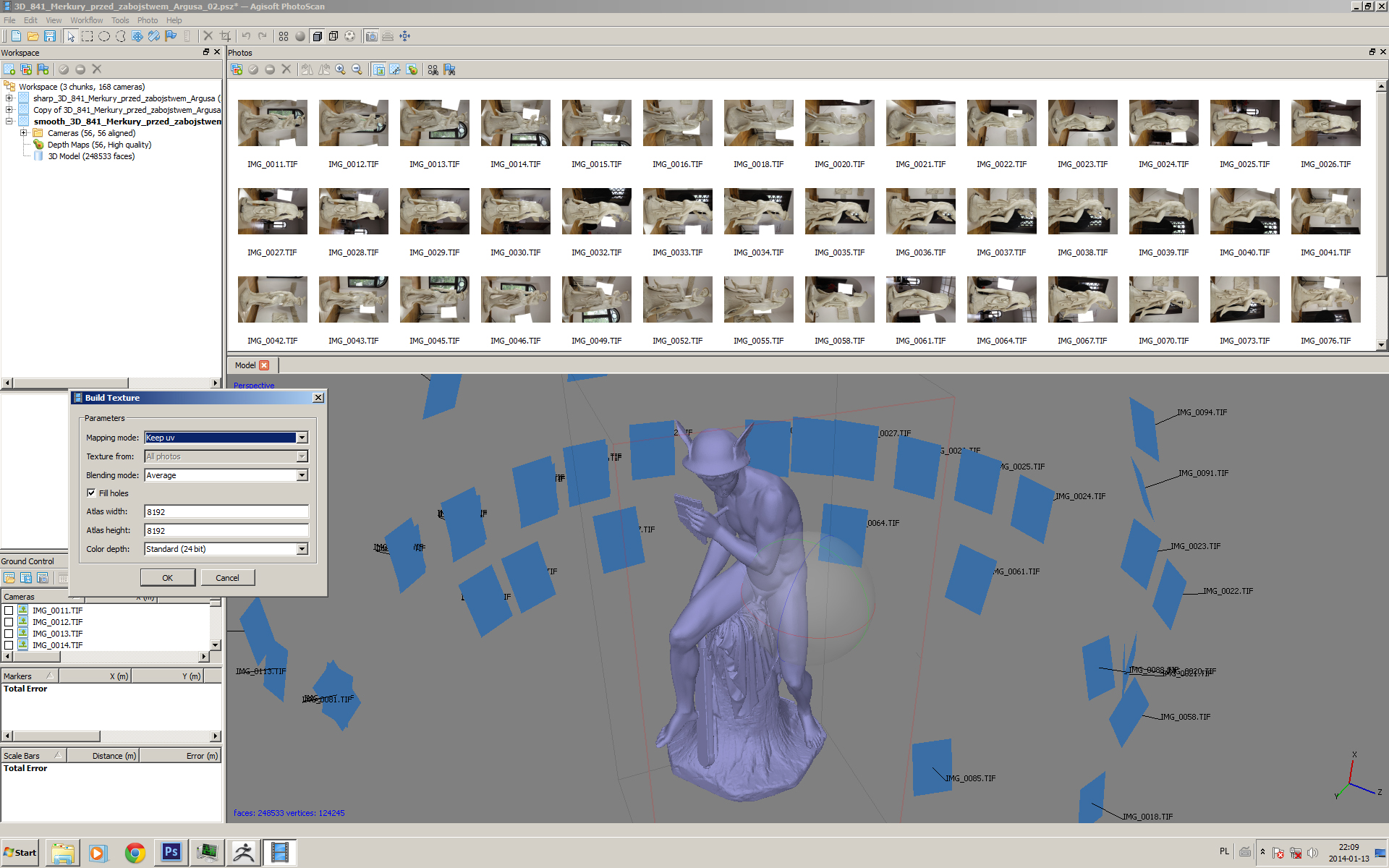

Photographs are collected with photogrammetry tools (Agisoft Photoscan, Reality Capture) into what are known as ‘colour textures’ but also 3D models, based on photos. That’s our second stream of data.

The next step is to combine 3D models from scanning and photogrammetry into one space, into one coordinate system. That concludes the process of semi-automatic editing of source digitisation data. Many digitisation projects stop here, because all possible data is obtained, and can be put into a safe repository.

However, the goal of our process is to have the best possible virtual representation of real objects and to publish it on the Internet, so now our Editeam has to judge all errors and artefacts of the semi-automatic process, and decide about the range of manual processing.

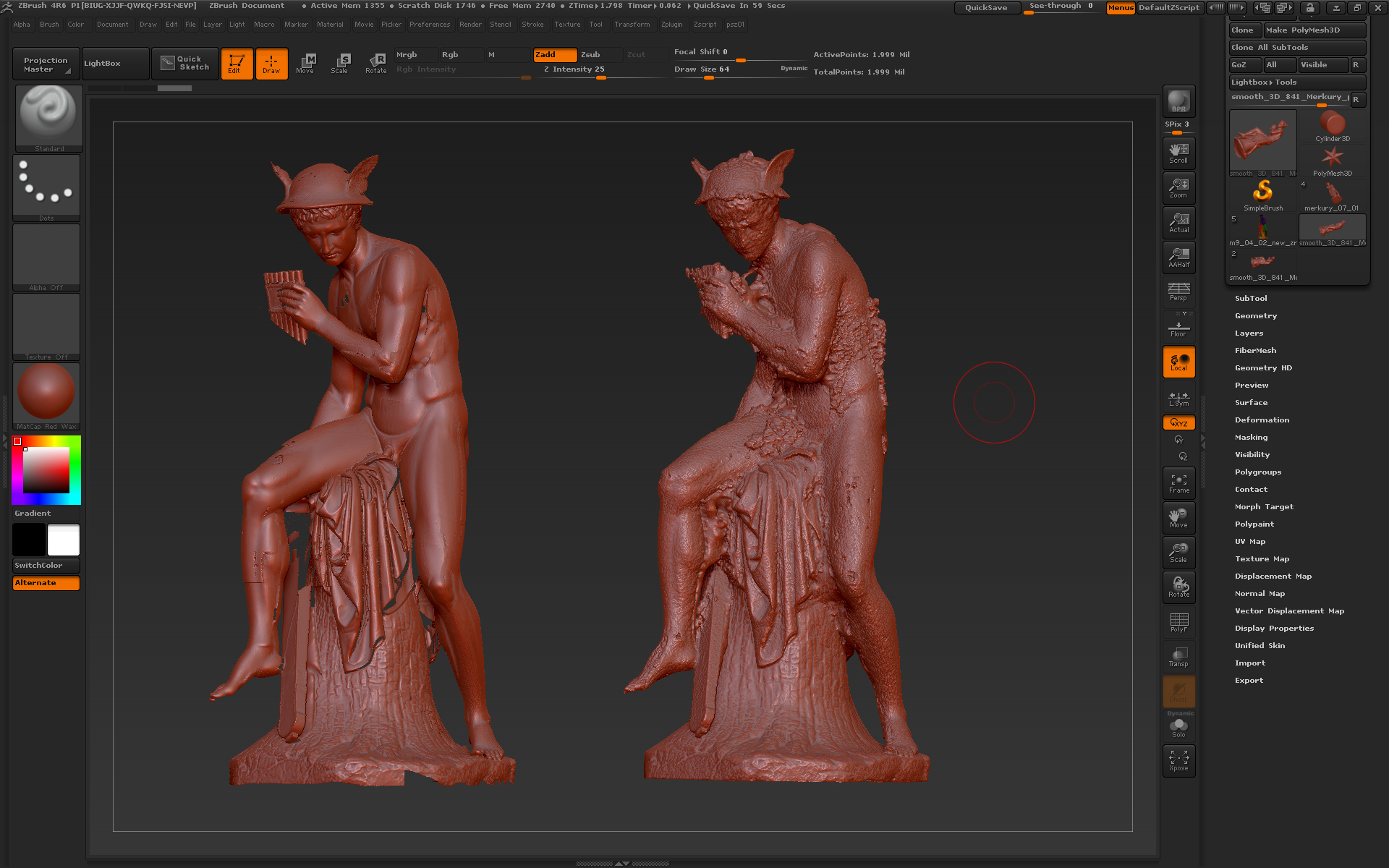

The manual phase starts from creating a draft three-dimensional model at the beginning, with several iterations, which, if necessary, aims to rebuild, alter and delete digital errors, as well as the additional painting of surface colour in the software, which enables virtual, three-dimensional sculpting and painting. For this part, we extensively use ZBrush but also Mudbox, Blender, 3ds Max and, lastly, MODO.

As a result, we achieve a virtual representation of the real exhibit as an accurate three dimensional, high resolution model. However, such high-quality material can only be properly seen by using graphical workstations and the appropriate software. Optimisation, which is the reduction of both geometry and texture resolution, is necessary in order to make it possible for Internet users to have access to the virtual exhibit. This is done by using numerous techniques, thanks to which it is possible to publish the three dimensional visualisations on the Sketchfab and Malopolska’s Virtual Museums website.

Process of manual editing main steps:

- Fig. 4 Manual editing process: photo sequence with Alpha channel

- Fig. 5 Manual editing process: Agisoft Photoscan – 3D data from photogrammetry

- Fig. 6 Manual editing process: Geomagic Wrap – scan registration

- Fig. 7 Manual editing process: Geomagic Wrap – ready mesh from scanning

- Fig. 8 Manual editing process: Pixologic ZBrush – mesh from scanning vs mesh from photogrammetry – visible artefacts of both methods

- Fig. 9 Manual editing process: Autodesk 3ds Max – rebuilding crucial parts

- Fig. 10 Manual editing process: Pixologic Zbrush – combing all geometry together

- Fig. 11 Manual editing process: Pixologic Zbrush – ready high resolution mesh

- Fig. 12 Manual editing process: Pixologic Zbrush – decimating and UV mapping

- Fig. 13 Manual editing process: Agisoft Photoscan – final texturing

- Fig. 14 Manual editing process: Pixologic Zbrush – final touch

- Fig. 15 Ready publication on Malopolska’s Virtual Museums website

List of tools used:

Hardware & Software

Data acquisition:

Multiview and turntable photography with Canon EOS (5DSR, 5D Mark III), shadeless tent and Bowens Light System

Structured white light scanners: HDI Advance, Artec Eva.

Data processing:

Photogrammetry processing: Agisoft Photoscan and Reality Capture.

Large 3D data sets processing: Geomagic Wrap, Meshlab

3D Data editing:

Pixologic ZBrush, Foundry MODO, Autodesk 3ds Max, Blender (based on operator’s personal need)

Texture editing:

Adobe Photoshop, Substance Painter, Autodesk Mudbox

Back to Reality. The Benefits of Digitisation

Veit Stvos CASE STUDY.

There is always the question of what to do more than just publishing, to engage viewers with the effects of digitisation.

One spectacular example of its use was the preparation of a 3D model and the photographic documentation of a priceless late Gothic bas-relief created by Veit Stoss, a well-known medieval sculptor. During the Second World War, this extraordinary object was hidden by covering it with a thick layer of polychrome, and it stood unrecognised in an old church in Ptaszkowa. But, after discovering it, it was obvious that an artwork of this class required storage under controlled conditions.

The model created by our Team made it possible to print a copy of a sculpture using 3D techniques and place it in the church at the original location. The original is safely exhibited at Nowy Sącz District Museum. 3D representation of this artwork can be compared with other objects from different museums on the Malopolska Museums website, with a new contemporary interesting story to tell.

- Fig. 16 3D Print of Veit Stvos sculpture by MonkeyFab (photo by mokeyfab.pl)

- Fig. 17 M.Pawlowska and J.Walczak at work on the replica (photo by Archiwum Pawlowskich)

- Fig. 18 Relief “Agony in the Garden by Veit Stoss vs other similar objects from different collections from Malopolska’s Virtual Museums website

“Little Thing” competition CASE STUDY

After gathering a complex and diverse repository of digital exhibits, and reaching a critical mass number of objects, a resource such as Malopolska’s Virtual Museums has became a source and an inspiration for new creativity, especially when the rights to use digital images of objects are in the public domain.

In 2017, our digitised materials became the basis for the “Little Thing” contest organised by the Krakow School of Art. The goal of the competition was to design a usable item that could become an attractive gift. Of course, the form of the project was to refer to the cultural heritage of Małopolska, presented via objects on our website. Over 70 entries were submitted, and the results exceeded our expectations.

The main prize in the Designed 2017 competition went to Martyna Piątek’s entry: a wine cork, inspired by maces from the Wawel Royal Castle:

Distinguished entry, Paulina Bielaszka’s lamp design inspired by the Bow Harp from the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow.

Sketchfab. Perfect Result at the End of the Process.

Both our processing and post-processing proved useful in the digitisation of various objects from Małopolska’s museums. But, our work would be incomplete without being able to show the effects of this work. When we launched the Małopolska’s Virtual Museums website in 2013, we chose Unity3D as the display technology for 3D models. Two years later, Google, Mozilla and Apple announced that they would disable the plug-in architecture in their browser support. We were left with over 400 models that we could not display properly.

Then, I came across Sketchfab, which turned out to be great as the final step of our 3D process, the best way to display advanced 3D materials on the Internet. And even more: Sketchfab is free for heritage institutions, and has huge support from social media. We had no doubts that the effects of our hard work should be transferred here and presented in such a great group, among many other excellent creators of digital heritage.

Paweł Szelest

Małopolska Museums Website / Virtual Małopolska Museums on Facebook