About the RCPSG

Hello! My name is Kirsty Earley and I am the Digital Heritage and Visualisation Project Officer at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. As an organisation, the College has provided support and training for medical practitioners for over 400 years. During that time, members and fellows of the College have contributed to its heritage, creating a large archive, library, and museum collection. It is my job at the College to ensure that the heritage is presented in a digital and interactive manner!

My background is funnily enough not in heritage. I am an anatomist and medical illustrator by training and completed a Masters in Medical Visualisation and Human Anatomy at the Glasgow School of Art. It was during this course that I began my career in 3D design and development.

My MSc project was to generate interactive 3D digital models for an online learning module in medical heritage. The items to be digitised were those belonging to the museum collection of the College, and were all significant tools in the history of medicine and surgery, such as Joseph Lister’s carbolic spray, William Macewen’s osteotome, and a dental key. Attempts were made to scan the tools via photogrammetry, however the specularity of the items proved to be a barrier and resulted in very distorted 3D models. The final solution was to create 2D panoramic models that could be rotated at will by the user.

This project was the inspiration for further experimental visualisation work at the College. As a museum, we have a limited physical display space, which can only hold a small percentage of our collection at any one time. In addition, access to the display space is limited because we are a working medical and surgical college, without a discrete public museum space. This just means we have to be more creative and flexible in how we provide access to our collections—digital visualisation is a great way of doing that. Hence, we pride ourselves in having an active online presence and providing interactive and innovative digital content to communicate our heritage. Part of our work is to also show to the cultural sector that effective digitisation and visualisation content doesn’t require ridiculously expensive equipment.

Workflow

For capturing 3D content, we have to adapt our scanning set-up to the limited available space on our premises, and there is no formal scanning studio. This means that our equipment has to be relatively portable! For lighting the item, a standard light tent is employed alongside some LED lights. We make use of a lazy Susan/home-made turntable to rotate the item being scanned. With regards to cameras, a standard DSLR camera is used with a tripod and polarising filter, when needed.

Scans are processed using Agisoft Photoscan (due to its free academic licence!) and further modified in Meshmixer.

Thanks to Sketchfab’s built-in AR feature, we have been able to show our collection items during public outreach events and give visitors control of the heritage they are experiencing.

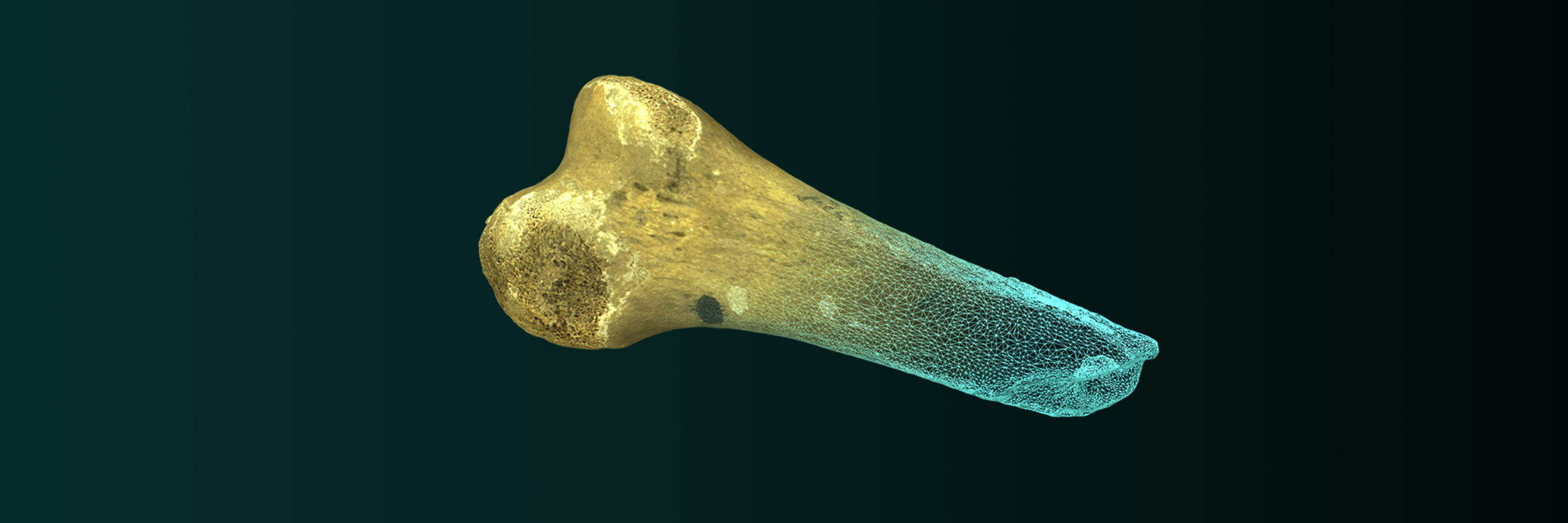

One of the best 3D scanning success stories is that of the replica cast of David Livingstone’s humerus. David Livingstone was a medical missionary and former fellow of the Royal College, best known for his travels in Africa in the 1800s. During his travels, he was attacked by a lion, which resulted in a fracture to his left humerus. Being the only medical person on site, Livingstone had to attend to and set his own wound—something that no practitioner would want to do! Unfortunately, he set the humerus almost 180 degrees out of sync and had limited mobility in his arm for the rest of his life.

When he passed away, his body was brought back to the U.K. for burial and later exhumed for identification. A team of doctors in London were able to identify his body due to the obscure anatomy of his left humerus! A plaster cast was taken of his arm and replicas can be found all around the U.K. Our cast of the humerus was one of the first items in the College’s collection to be 3D scanned and it was also 3D printed by the Glasgow Science Centre. This project is a perfect example of how we have used 3D scanning to communicate our heritage in an interactive manner.

Challenges

The main challenge that we faced when scanning items is the fact that most of our items are made of metal and/or glass! Due to the issues regularly faced with highly reflective materials, only a small portion of our collection can be scanned. Although it’s possible to apply a spray coat to the item to reduce specularity, it’s still a bit of a controversial subject for conservators, so for now we are trying other solutions.

Specularity also causes the textures of some of our scans to be of lower quality than we would like. That’s why I’m now looking into enhancing the quality of textures through post-processing softwares, such as Substance Painter, for painting and baking textures.

Advice

What advice would I give to someone thinking about 3D scanning for heritage collections? Just try it out! The 3D scanning community can feel quite intimidating at first, but really it’s all about experimenting and helping each other out. Don’t be afraid to ask questions to members of the Sketchfab community and don’t be afraid to embrace modern technology in your cultural institute.

I think some cultural organisations can be skeptical towards using digital technology for fear of the digital replacing the artefact. But that’s simply not the case. Heritage organisations should embrace the digital to enhance the stories of their collections, not to replace them. Use digital products alongside physical items to provide more learning opportunities and avenues for visitors.

The future of 3D in cultural heritage is exciting and not only limited to heritage institutions with lots of financial resources! As technology becomes cheaper, adopting digital strategies in heritage becomes easier. One can only imagine what will be created as research continues.