About

The Centre of Digital Humanities Research (CDHR) sits in the Research School of Humanities and the Arts in College of Arts and Social Sciences at the Australian National University. It’s a dynamic Centre, where staff and students work across diverse research projects. These range from 3D modelling, to digital mapping, Linked Data, and Indigenous art and culture. At the ANU there are researchers across a range of disciplines engaged in exciting digital-led research that intersects with the cultural heritage sector, from creative coding in computer science, to digital literature and interface design for engagement with cultural collections. We also enjoy a close proximity to Australia’s national cultural institutions, with researchers and students currently engaged on projects with the National Museum of Australia and National Library of Australia.

The Centre’s 3D work is predominantly focused on the work of two academic staff, Dr Terhi Nurmikko-Fuller and Dr Katrina Grant. Terhi’s first work with 3D modelling was on cuneiform tablets housed at the British Museum, a collaboration with Dr Jon Taylor and Daniel Pett. Since then, she has created 3D models of boab nuts carved by the Indigenous artist Jack Wherra for the National Museum of Australia, and helped create a 3D digital replica of the Black Rod at the Australian Senate.

Skullbook and Other Projects

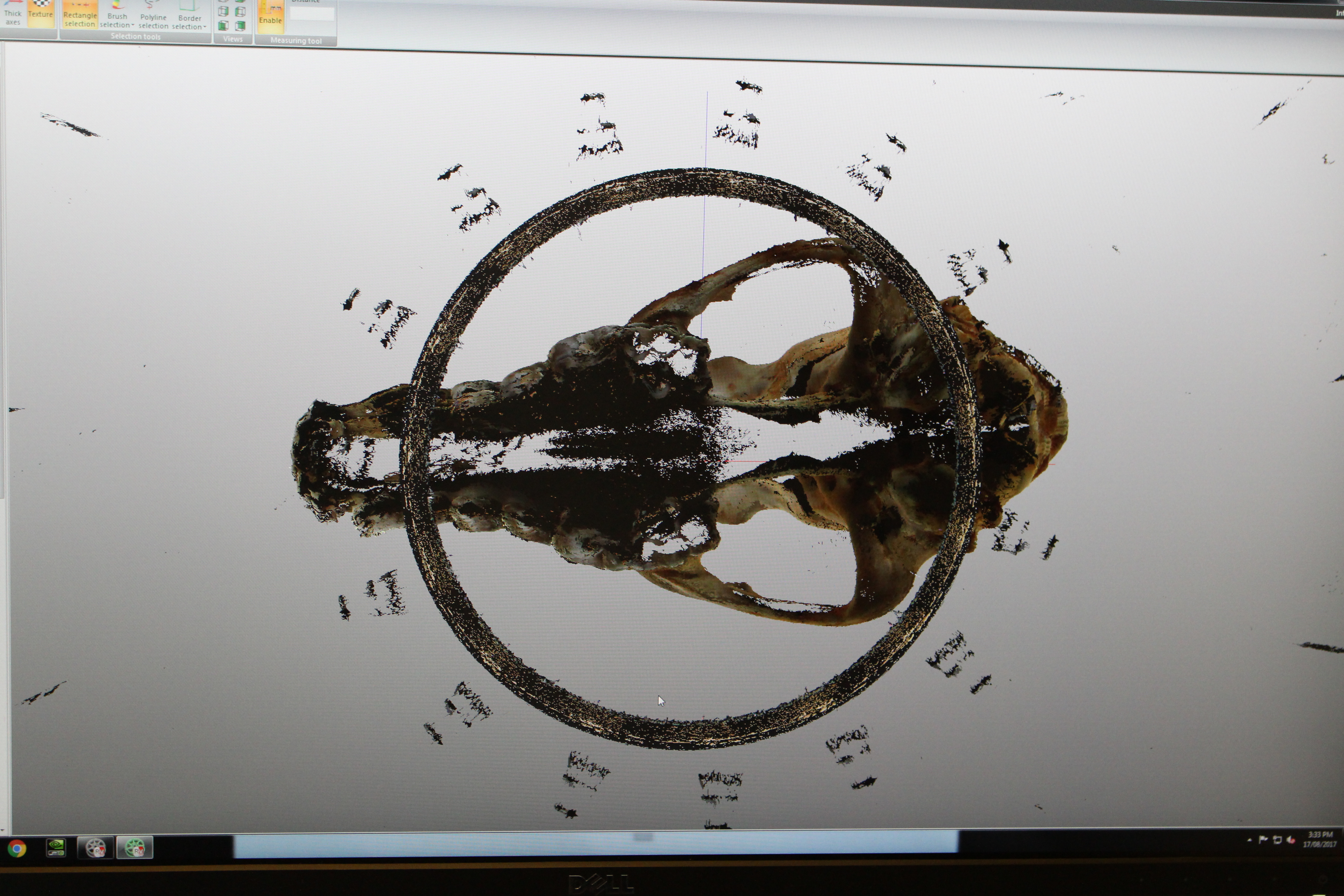

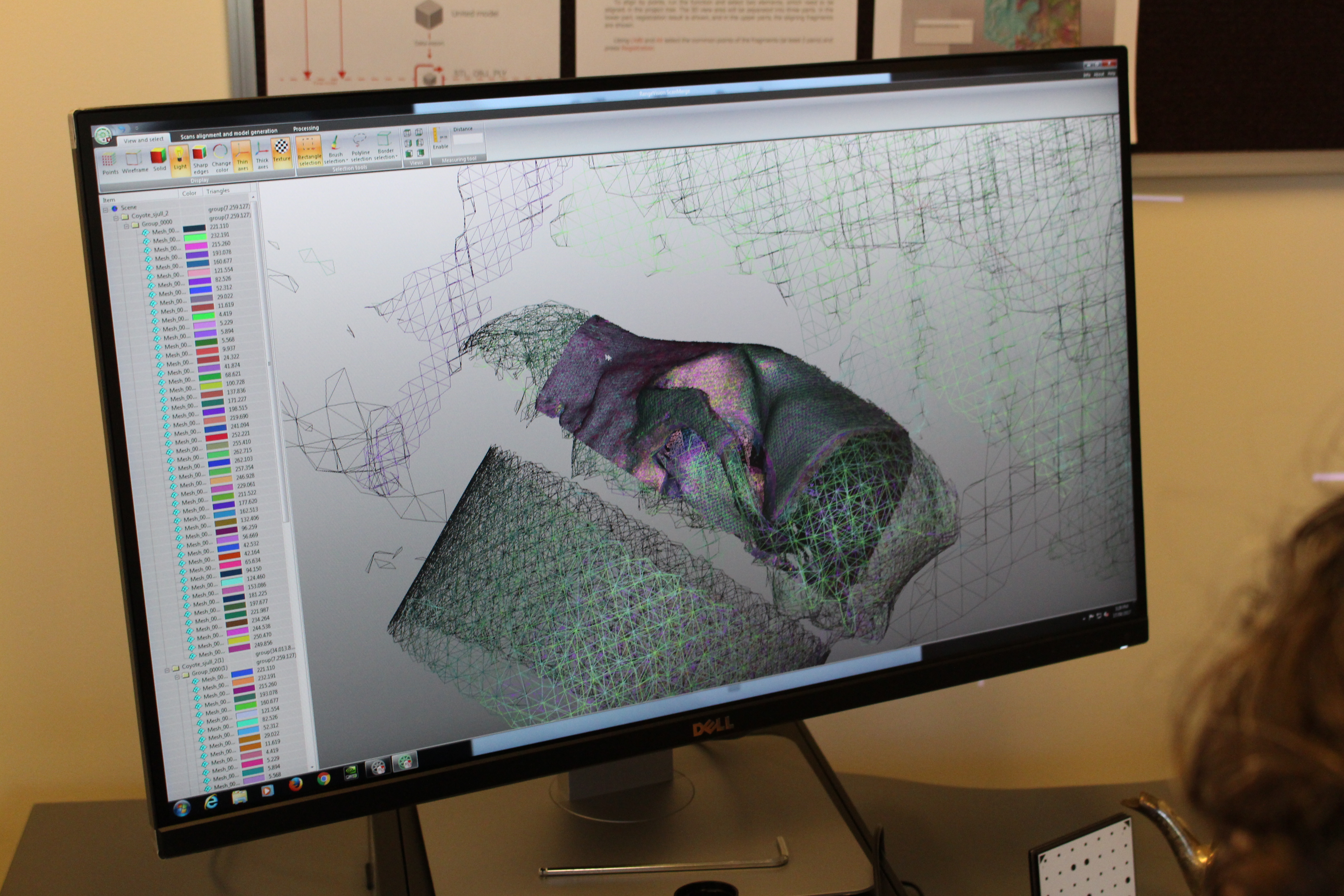

Terhi and Katrina are working on the Skullbook project, together with an archaeologist and a zooarchaeologist from the ANU’s School of Archaeology and Anthropology. A small grant to support innovative teaching meant that one of the CDHR’s PhD students – Renee Dixson – could be hired as a Research Associate to do much of the 3D modelling, including developing a workflow for 3D model development with a Rangevision Scanner. The aim of the project has been to pioneer new approaches to object-based teaching, where digital replicas allow for greater access and support student learning. The initial project produced 3D models of animals skulls, which students of archaeology and zooarchaeology will use to develop their ability to distinguish between a range of animal skeleton remains that are frequently found in large quantities at dig sites. The models exist both as a digital resource (open access!), and as 3D printed objects that they can handle.

Katrina has also recently been involved with creating 3D models of archaeological objects held at the Classics Museum at the Australian National University and supporting colleagues in art history to develop 3D models of objects to support digital exhibitions and object-based teaching.

Before working with 3D modelling in cultural heritage, Terhi was completing her PhD at the University of Southampton, UK, where she was a member of the Archaeological Computing Research Group. During this time, Terhi gained some experience working with reflectance transformation imaging, and it was through this that she moved into photogrammetry, and then started experimenting with automated workflows for 3D model production.

3D for Education

The CDHR teaches 3D model creation (to students and academic staff); we have worked with a range of collections (from animal bones to Greek pottery to Australian Second World War relics) to teach students the process of model creation using photogrammetry and 3D scanners. Our students come from fields across the university, including history, law, computer science, social sciences and art history, all with an interest in understanding how 3D objects are made. For some their interest is in how these digital objects can be used for teaching (as with the Skullbook project). Focused teaching is a growing area of interest across the humanities, and 3D content offers support for this. Other uses include outreach for collections—Australia is geographically vast, and many people lack ready access to our key cultural collections (school children from Perth, for example, are unlikely to visit our National Museum in Canberra, located almost 4000 kms apart!). Museums and galleries, and the students training to work in them, are interested in how 3D objects, both digital and printed, can be used to bring these objects to more diverse audiences.

Tools and Workflow

At the CDHR we focus on two distinct workflows for 3D model creation: photogrammetry, and an automated workflow using a RangeVision 3D scanner. For the photogrammetry, we combine a digital SLR camera, and a Foldio lightbox with an associated turntable (or other appropriate lighting depending on the object type). This workflow has been used to create the models of cuneiform tablets from the British Museum, boab nuts from the National Museum of Australia, and some objects from the Classics Museum at the Australian National University. The RangeVision scanner was used on the animal crania for the Skullbook project, and for the ceremonial Black Rod from the Australian Senate.

When comparing a largely automated workflow enabled by the RangeVision 3D scanner to the more manual process of photogrammetry, the latter has several benefits for beginners. This is for a couple of reasons: first, because most people will have some experience of photography, and so the learning curve is less steep. Second, as a manual process, it requires you to get more involved in the process itself. Third, it is cheap! Automated 3D scanners are expensive and likely out of reach for many cultural institutions who don’t have much cash for digitisation. Photogrammetry can even be done with a decent phone camera (like an iPhone 6 or a Google Pixel). We are keen to show that 3D modelling is a skill that can be learned and used by a wide range of people and organisations as a way of sharing our culture and making research materials more accessible.

Challenges

There have been two kinds of challenges in our work with 3D materials. The first is the challenge of the object – these items are often fragile, unique, and some are thousands of years old. Others have specific social and cultural value that far exceeds their monetary cost. The scanning of the animal crania required a close attention to detail. For these 3D objects to fulfil their role in training, archaeologists required a high level of detail that would allow users to discern the shape of teeth and see the shape of small interior bones. This high level of detail is beyond what is often required for museum 3D objects. Other objects present challenges that most 3D scanners, photographers, and photogrammetry practitioners would be familiar with: the smoothness of the object surface, reflective materials, very thin objects, and so forth. For example, the Black Rod from the Australian Senate has a silver crown with an intricate detailed carving. The level of detail and the shiny surface made it a difficult object to capture, but we love a challenge and were extremely pleased with the outcome.

A second challenge centres on intellectual property rights, which is a well-recognised issue in the creation of digital cultural heritage. Who owns digital copies? While our preference is to make 3D models open access under a CC license (such as CC Attribution), this is not always possible in a collaboration. Often each institution has a different approach and we tend to resolve these intellectual property and copyright issues on a case-by-case basis.

The Future of 3D and Museums

3D digital objects have such wonderful potential to allow people who cannot access the objects directly to engage with them. Even those members of the public who are able to see an object in the real world by visiting the museum that holds them will only be able to see the object through a glass, with no opportunity for interaction. They will not be able to hold it, turn it, twist it, tilt it, or expose the reverse. With a 3D object displayed on Sketchfab, they can do all that. This alone will be a game-changer.

Another consideration is that these 3D models can be printed out as 3D objects, which in turn can be used in handling sessions. They can also be used, as in the case of the Skullbook project, for teaching. And certainly for those of us who love a good museum shop, being able to take home a version of a favourite object would be amazing.

Sketchfab

Having spent several years working with on a range of quite diverse projects, we are always impressed by people who have managed to capture a complex object, or a challenging surface (like shiny reflective silver).

CDHR Twitter / Terhi Nurmikko-Fuller’s Twitter / Katrina Grant’s Twitter / CDHR Facebook / CDHR Instagram / CDHR Website