About

My name is Kevin C. Nolan, and I am the Director of the Applied Anthropology Laboratories (AAL), an outreach arm of the Department of Anthropology at Ball State University. The AAL provides a full range of cultural resource management (CRM) and research services. Our professional staff is experienced in all levels of field survey, excavation, analysis, and curation. Our staff specializes in geoarchaeology (geochemistry, geophysics, etc.), spatial analysis, faunal analysis, and a variety of other research specialties. We assist communities, government agencies, and industry in the integration of archaeological research with community and economic development. We work closely with our partners to meet their needs from project inception through completion. While delivering quality, state-of-the-art services to our partners, we also provide thousands of hours of hands-on training for students in Anthropology. Our student employees build a strong record of applying their knowledge in real-world professional situations, preparing themselves for employment upon graduation. Our motto is “Learn. Work. Discover.”

My research interests include archaeological survey methods, geochemistry, settlement patterns, and public engagement with archaeology. I personally became interested in 3D modeling as a way to reach new audiences and preserve things that are not housed in museums, and share the accumulated knowledge of history with the general public. My training has come primarily from working directly with the hardware (NextEngine) to acquire digital models and talking with a community of users (including Dr. Bernard Means and Dr. Michael Shott) about issues encountered.

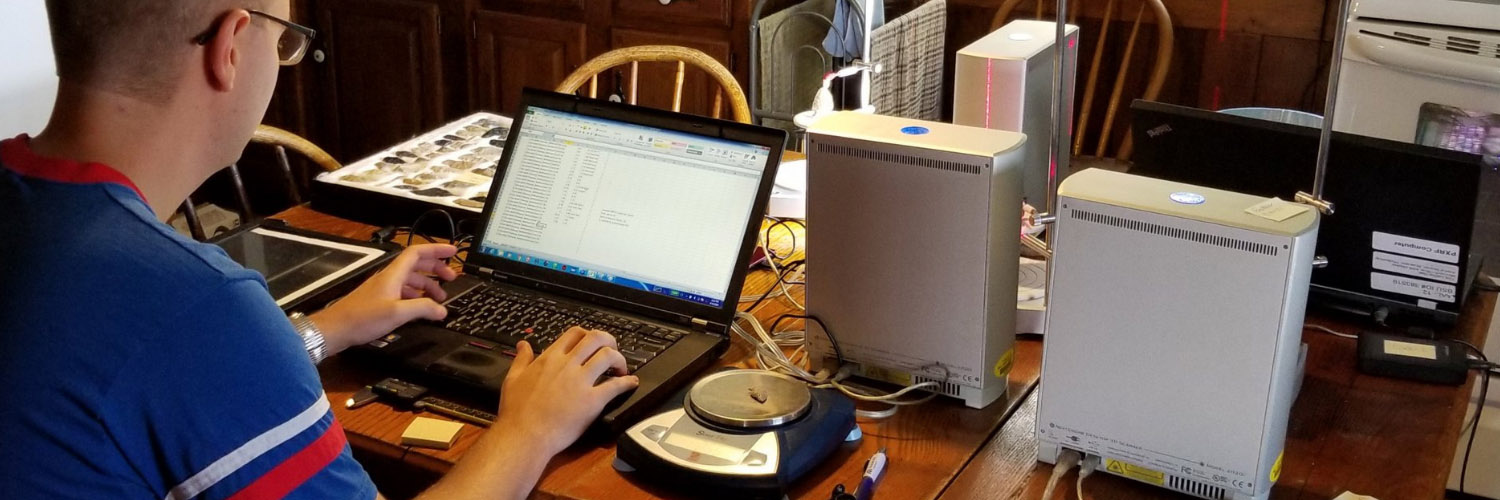

I got into 3D modeling for archaeology in 2009 when I started building a collaboration with Michael Shott of the University of Akron that eventually resulted in our collaborative NSF-funded project COADS, documenting approximately 20,000 artifacts from hundreds of sites in private collections in central Ohio. After initially sparking that interest, the AAL was first able to acquire a couple of NextEngine scanners through a project (SCHoN) to analyze museum collections associated with the Hopewell societies of central Ohio. Once the scanners were acquired, we started to use them whenever we could to document things from other projects and disseminate the results of our work to a wider audience (e.g., HPF Grant Projects, the Dolan collection).

Why 3D?

We use 3D models for multiple purposes. Sharing the models of the real, but often inaccessible parts of the past with the public fits with our public education mission, and serves to engage more members of the public in archaeology and preservation more generally. We use these models in presentations to local school classes as digital models and 3D printed replicas, so 3rd and 4th graders learning Indiana and Ohio history can tactilely experience history. It is also part of the AAL’s efforts describing and exploring the history of technology in the past. As part of the COADS project (this aspect led primarily by Dr. Shott) we are conducting geometric morphometric analyses on hundreds of 3D and thousands of 2D models to learn about the functional and cultural constraints (e.g., trends, fashions, teaching traditions, acceptance of innovation) placed on tool manufacture through time in central Ohio. We also use this technology, particularly paired with Sketchfab, as a way to share raw data with collaborators and the interested public. Where possible, all of our models are free to download and can be used for any purpose, research or otherwise (hopefully with appropriate attribution).

One particular project, COADS, illustrates the merger between public engagement, collaboration, education, and research. Recognizing that members of the public with an interest in archaeology have materials and knowledge to contribute to a comprehensive understanding of local and regional history, COADS engages individuals with private artifact collections to collaboratively incorporate their knowledge into a synoptic narrative. We recruit collaborators who agree to allow COADS to analyze and digitally record their private collections. We create 2D images of all of their diagnostic (i.e., produced for a limited and know period) stone tools and select a random sample for 3D scanning. All artifacts are retained by the collector, yet their knowledge and decades of work contributes substantively to a cumulative record of local history that can be shared with the everyone. We share the models thus created with geographic information so anyone can see the tangible history of their local area. These models, most freely available for download and reproduction, can be used in public outreach events to generate interest in history, in K-12 classrooms to help engage students in the history, and in university classrooms in a variety of ways. These models also constitute raw material for research by ourselves and other interested scholars.

Tools and Workflow

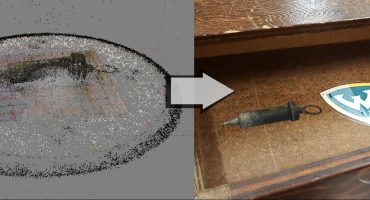

All of our modeling is currently done with a NextEngine HD or Ultra HD laser scanner. We built our protocols off of those recommended by Dr. Means, with some adjustments based on our own experience. We generally use 6-8 divisions for most types of artifacts scanned. Once the model is acquired, trimmed, and fused, we export to PLY and OBJ formats for portability and sharing. If additional editing is needed, we generally use Meshlab. We also perform measurements in Meshlab, and have used Rhino for some advanced editing and reconstruction tasks (e.g., refitting or extrapolating a ceramic vessel).

Our biggest challenges have been mostly with software glitches and models not aligning. Occasionally we can fix alignment problems by going into a scan family in ScanStudio and aligning individual scans, but often it is easier and best to simply re-acquire the scan. This is more complicated when we are on a time limit, as with a remote visit to a private collection or a museum, and the model editing is of necessity done after the fact back on our own lab. Lacking the actual object, sometimes scans are lost entirely.

I would encourage anyone interested in public education for heritage to engage with 3D models, and particularly to share models publicly and provide context about the original objects’ history. Public libraries, schools, and other public institutions often have 3D printers now, offering a unique opportunity for engaging a wider audience in preservation and learning about history in new ways. Sharing models so people can print them, or even organizing events at libraries or other places with printers is a good step for engagement. Bernard Means has a great model of public engagement with 3D models and printed replicas. This is something that we aspire to and are building capacity and support to replicate some of his success at engagement. While there are myriad research opportunities for 3D models of artifacts, I view the public engagement piece as one of the most important. With this technology we can take the things hidden in museums or basements and share them with the world. This approach liberates historic preservation from geography and makes it easier for everyone to experience a little piece of the past.